The Sentinel

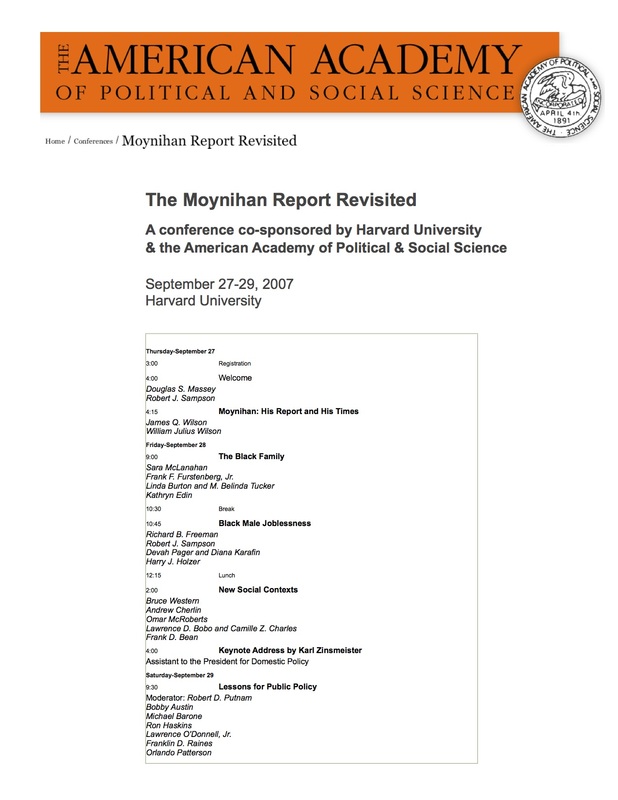

By Karl Zinsmeister

Remarks to conference “The Moynihan Report Revisited”

American Academy of Political and Social Science

and Harvard University

September 28, 2007

I’m very happy to be here—not least because I’ve been told that the office I occupy at the White House is the same one used for a time by Pat Moynihan during his West Wing years. Karl Rove once tried to explain to me how Moynihan had faithfully extended a long White House tradition by leaving a bottle of whiskey in the office closet for his successor. I seem to recall Karl saying something about Pat carving his initials in the office woodwork too, again extending a hoary old practice.

But I’m afraid that all went in one ear and out the other. I’m not really that kind of conservative, and probably won’t be stashing any traditional bottle or engraving beams during my tenure.

Nor does all of that ring especially true to my ear as Moynihan behavior. The fellow I knew was definitely not to be trusted with a penknife. And if he somehow got hold of one I believe there’s a much higher chance there would have been Irish blood on the rug than initials on the beam.

The whiskey part I think I’ll just skip right over. Although it is possible the dear man may have left behind an empty bottle.

I’d like to state, here at the beginning of my remarks, how appreciative I am to have been included in this distinguished group of researchers, and thinkers, and solvers of national problems. As I scanned the list of presenters at this conference it occurred to me that squirreled away in my personal book collection are perhaps 15 different volumes with one or another of your names on the spine. The persons in this room have taught me—and many other Americans—some of our most important lessons in social policy, and I am honored to share this day with you.

I’m quite certain you could have engaged a more fascinating keynoter, and have to assume my presence here reflects the difficulty of finding someone else who matches the odd Moynihan template: lifelong New Yorker, having a Syracuse connection, with a history of crossing party boundaries, and White House experience slinging domestic-policy advice, to a Texas President. There are only a few of us who can tick that queer combination of boxes, so it may just be runaway historical homage that got me invited here.

In any case, I’m pleased to have this opportunity to pay my respects to the memory of Daniel Patrick Moynihan—who offered me my first job out of college, launching me into the work of Washington. (And please let me enter into the record here that I am speaking for myself, not the President, in all of my remarks today.)

*****

When Teddy Roosevelt said that “nine-tenths of wisdom is being wise in time,” he was thinking of the disappointments of becoming wise too late. Pat Moynihan demonstrated that being wise early also carries certain risks. The thing I most admire Pat for is his work as a kind of intellectual sentinel, as a spotter of significant trends not yet noticed by others, and a ringer of alarms. “He who marries the spirit of the age will soon find himself a widower,” warned Chesterton, and I believe Moynihan’s intellectual fertility grew particularly out of his resistance to fashion and group-think. His personal independence and intellectual autonomy allowed him to cogitate his way through problems without getting distracted by herd movements.

As an example, one of the first projects he set me to work upon as a young Senate aide was research on whether American girls were reaching menarche earlier than females in other times and other societies, and whether this might be an influence on elevated teen childbearing and welfare receipt. I assure you, there weren’t many other Senators or Senate aides clamoring right then for information on precocious menstruation. I had that part of the Library of Congress pretty much to myself. But Moynihan didn’t care if no one else in America could even spell menarche, much less link it to the work of the Senate Finance Committee. If he thought it might be an influence on an important social problem, he wanted to know more.

I don’t want to romanticize, so let me note that Moynihan’s unpredictably ranging mind could often frustrate. There’s a probably apocryphal story about Immanuel Kant and Johann Goethe taking a walk one day to discuss philosophical matters. When they returned, Kant was asked if he found the time enlightening. “I’m still confused,” he is said to have answered, “but at a much higher level.”

There were times when Moynihan confused his colleagues at a very high level, often because he seemed to be of two minds. During his four Senate terms, Moynihan frequently provided talking points for conservatives while voting with liberals. And at times there was some cognitive dissonance.

It reminds me of the father who counseled his daughter, as she headed off to a border-state college, on types of men she might meet. Northern boys, he suggested, were likely to be active and propose interesting dates. Southern boys would often be romantics, perfectly happy to just walk in the moonlight. To which the daughter answered, “I think I’d like to have a Southern boy from as far North as possible.” Sometimes Pat Moynihan seemed to be trying to straddle lines in similar ways.

But for sheer breadth of mind, the man was a delight. Those of us who have resisted the modern tendency toward occupational specialization and instead tried to build careers connecting dots between demographics and economics and religion and history and culture can take comfort from the wide swaths of intellectual life that Moynihan ranged across. My commute to the White House involves bicycling the length of Pennsylvania Avenue every morning and evening, and as I survey the ways that boulevard has revived since the days when Pat Moynihan made rescuing it one of his many projects (back in the early days of the Kennedy administration), I think to myself that this alone would be a pretty good life’s monument.

But of course Moynihan’s accomplishments extended far beyond revitalizing that national corridor, and far beyond his other achievements in architecture and urbanism. He also mastered foreign policy. He was an expert on Social Security. He had a sage’s knowledge of India. He knew more about immigration, and race, and family structure than almost anyone of his generation.

At his best, Moynihan magnified his originality with a tolerance for risk. Those are two very rare—I’m afraid increasingly rare—qualities in Washington. There was a major-league baseball player named Zeke Bonura (who, perhaps fittingly, ended his career in Washington with the Senators) who figured out years ago that under baseball’s rules you usually won’t be charged with an error unless you touch the ball. So Bonura simply avoided any play that looked the least bit difficult, and in this way managed to lead the league in official fielding percentage.

While risk avoidance can yield sterling individual statistics, it is bad for the team—which in the political realm means the nation. Moynihan understood this. In an interview in the spring of 2002 (the last time I saw him in person), I asked why it had become so difficult to build anything new in New York City. He noted that “in the 1970s, civic reputation began to be acquired by people who prevented things from happening,” warning that “many things get stopped for no reason” other than creeping timidity. In his most shining moments, Pat Moynihan was a living advertisement for risks taken in an effort to improve one’s society, and a walking rebuke to those souls unwilling to touch the ball for fear of making a mistake.

*****

Pat Moynihan’s most valuable service to the nation was to point out the central influence of family structure on individual well-being, group prosperity, and collective success. At the tail end of the Baby Boom, Americans were taking family stability for granted, and ignoring the evidence that household decay hurts many innocents, sometimes even dragging down entire communities. The conversation Moynihan started eventually convinced many citizens that the strength of our family bonds isn’t just a private issue, but a matter of essential public interest. His 1965 premise that the federal government should make family stability a central goal of its programs is now shared by widely varied political factions.

A good thing, too, because what the Moynihan Report identified as a minority virus soon became a mass outbreak. Today white families spin apart at rates higher than blacks exhibited at the time he wrote; the two-parent home has become a rarity for African-American children; and the unhappy sequels of disorganized households, absent parents, and unhealthy income gaps have become common. If a young American were placed behind a curtain and you were required to guess his or her social status and individual happiness with only one factual datum before you, the single most trenchant indicator you could ask for would be whether that person grew up with both parents in attendance. Unfortunately, about a third of our next generation will substantially grow up without this advantage, and fully half will have at least a brief brush with family separation before they turn 18.

The rapid spread of the family-decay virus outstripped our abilities to diagnose and prescribe. It’s not that we have stood still since Pat Moynihan dipped his toe in these waters in the mid-1960s. Large efforts have been made to transfer income, encourage work, compensate with public education, bolster responsible fathering, and otherwise mend the tears in our family fabric. These efforts have often been laudable, and sometimes helpful. But they have not made our problems go away.

*****

Of course we must keep trying. One place where I personally nourish hope for solidifying family life today is in efforts to strengthen marriages. The nub of our problem is that large numbers of fathers have become disconnected from their children, and languished in what once would have been called irresponsible bachelor behaviors. For most men, though, active fathering, diligent work, and social responsibility come as part of a package deal that is founded on the male-female dyad. The reality is that once their link to the mother has crumbled, relatively few fathers will stay heavily involved with their children (only 20 to 25 percent in the “Fragile Families” research, and less in some other studies). Similar falloffs appear in the upholding of other obligations and responsibilities.

The strongest influence leading most men to grow up and join the world is the desire to win a good lifemate. Hunger for a strong mental, emotional, and sexual partnership with a woman is the main force creating the good husband, good father, good employee, and good citizen. Conversely, in a world where marriages are falling apart, desirable male qualities like respect for women, mentoring of children, disciplined occupation, and social responsibility will also go into decline. And attempts to fix those secondary breakdowns without first fixing the marriages will not be very efficient. To put it simply: no solid marriage, no good family man.

More generally, psychologists and social historians like J. D. Unwin have suggested that rechannelling sexual energy into less self-interested undertakings—into constructive social activity—is a hallmark of successful civilizations. The institutions that do the rechannelling are invaluable to society. And the most necessary institution of all for accomplishing this is marriage.

Marriage also functions as a safety net for individuals. Evidence from history, examples from particular sub-populations, and patterns among immigrants suggest that where the marriage base is solid, households can weather economic setbacks and external pressures surprisingly well. But when loyalty to spouse and fellow parent crumbles, even a minor battering can bring misery.

The best antidote to the various social turmoils Moynihan worried over, then, may be renewed emphasis on enduring marriage. Yet any observer who pursues that proposition will quickly be struck by one thing: How little help is currently offered by society to reinforce marriage. The last I checked, research indicated that only about a fifth of all divorced persons received any sort of counseling or mediation before dissolving their marriage. Meanwhile, only about a third of all couples receive any formal marital guidance before exchanging vows. Pretty clearly, we have not done all we can to strengthen marriage as a vital civic institution.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer once counseled a young husband and wife that “it is not your love that sustains the marriage, but from now on the marriage that sustains your love.” That paradox is actively resisted by many proponents of today’s pleasure culture, who portray love as a feeling, rather than as a decision to befriend and stand by someone for the long term. In truth, however, marital stability need not conflict with pleasure. By keeping couples together, after predictable stresses arise, long enough to give them a chance to fall in love again, committed marriage actually serves individual delight and happiness.

I recognize that these notions are hard for some modern Americans to accept. The family-structure concerns that Pat Moynihan introduced into public consciousness 40 years ago are still being squelched with claims that family life is a matter of merely “private” concern—the business only of the persons directly involved. On both the left and the right there is a temptation to ignore contentious family issues in favor of more bloodless explanations for social problems.

On the political left, an automatic trope blames social problems and disparities on discrimination, with easy recourse to government action or the courts as the favored solution. Lapsing into this simplistic explanation, however, would undo the heroic Moynihan achievement—which was to make the nation understand that civil-rights guarantees alone will never be enough to pull lagging populations into mainstream success.

On the political right, the symmetrical mistake is believing that national prosperity is all that’s needed to erase social fractures. The truth is that the full-employment economy Moynihan dreamed about has mostly been a reality in the U.S. for more than a decade. My White House duties have included some intense work on immigration issues, and I can tell you that our most pressing economic risk today is not having too few jobs, but rather having too few willing workers for the jobs that need filling. Yet even as employers clamor, some U.S. sub-groups languish outside the mainstream workforce—for other than economic reasons.

Here is Moynihan reflecting—20 years later—on his mid-1960s insight: “The quality and decency of life in the United States…were incomparably greater than in years past. And yet there was a segment of our population whose lives had somehow not been touched by the general success…. Increasingly, family structure defined this population.”

*****

This problem has deepened in the years since, and shows up in many places. Here is one little example that whispers a warning to us: While children of divorce make up close to half of all American youth today, they are only around 10 percent of the students who enter our most demanding colleges. Even after adjusting for income, SAT scores, parental education, and so forth, children who experience divorce are only half as likely to attend a selective college. Clearly, many young Americans are seriously weighed down by their parents’s family choices, in ways that can be hard to overcome.

This is perhaps the deepest root of today’s inequality problem. Widened gaps between the most successful and least successful Americans rightly worry both liberals and conservatives at present. The weakening of family cohesion, and the damage this does to our nation’s “human capital,” especially children, is clearly a major driver of these disparate life courses.

I also worry, personally, about an even broader problem: the possibility that raising children itself may now yield economic disadvantages. Even steady workers and loyal spouses sometimes feel today that acting as a devoted parent can leave you behind other Americans in standard of living. Certainly changes in taxation have punished investment in children.

At the beginning of the Baby Boom, a typical married-couple family with two children paid only a few percent of its income in taxes. There was a consensus that parents rearing young children were providing an important service to society, and ought not be burdened with heavy taxes. Today, the typical family of four has more than a third of its income consumed by Federal income taxes, payroll taxes, and state and local taxes. It’s sobering to realize that the typical family now pays more in taxes than it pays for mortgage, health insurance, and transportation combined.

In the second half of the twentieth century, taxes rose much more sharply on families with children than on the childless. This primarily reflects the decline of the dependent exemption in our income tax system, plus rising Social Security levies. Recent tax cuts have trimmed the rate of Federal taxation on the median family of four by about 30 percent since the 1981 tax peak, but the tax demands on childrearers remain far higher today than during the first two decades after World War II. If the dependent exemption were set at the same fraction of income as in 1948, a parent could now write off about $15,000 for every child—instead of the $3,300 allowed by the IRS last year.

The expanded tax burden on families is exacerbated by recent upward spirals in the price of particular goods and services that are central to family life. For instance, families with children need more living space than other Americans, so the housing bubble that rocketed home prices upward over a decade has pinched parents even more than others. Medical care is likewise something consumed by all citizens but in higher quantities by childrearing families, so, here too, a generation of exaggerated cost spikes has pressed doubly hard on parents. A final inflationary spiral especially disadvantaging Americans raising kids is college costs—which soared by almost 300 percent over the same recent period when medical expenses jumped 200 percent, food rose 80 percent, and clothing inflation was 20 percent.

The cumulative effect of these economic turns has been to leave families feeling less well off. At the same time, an economic boom lasting nearly a generation has offered child-free Americans record prosperity and opportunities for consumption. Adjusting the economic advantages of non-childrearers versus childrearing households may be a task future policymakers will want to consider.

Mind you, this is not a matter of pitting one group of Americans against another, because nearly all us spend many years in both kinds of households. The question is simply whether it would be good for the nation if a certain amount of economic burden could be shifted off the shoulders of those raising children while they are in the middle of what has aptly been called “the parental emergency.” That would of course mean transferring some load elsewhere—to those same Americans during the years before and after they focus on children, as well as to the small number of Americans who never raise children. Since childrearers are not only producing America’s future citizens and inventors and soldiers, but also the workers who will pay the Social Security and Medicare bills of today’s footloose adults, offering support and encouragement to parents would seem to be not only fair but also sensibly businesslike. Parents are the ones who keep social-welfare transfer systems solvent in the long run.

*****

I’d like to end on something of a positive note. Not to make you feel good, but because pessimism about American society usually ends up being embarrassingly inaccurate. Just as an empirical fact, the reality of U.S. history has been that most of this country’s social and political problems have eventually ended up improving—often in surprising and speedy ways. As I re-read “The Negro Family” for this conference, I couldn’t help but feel that Moynihan’s report was somewhat over grim in ways that date it and make it less “true.”

His set-up to the report’s final paragraphs famously warns that “the tangle of pathology is tightening.” And in 1965 it still was. But just a half-generation later, few observers believe, as then, that “this problem may in fact be out of control.”

The tide toward welfare dependency that once seemed irresistible has crested. More than half of all African-Americans now own their own homes. A traumatic national crime surge has been tamped down. Six out of ten black youths are in college the year after they graduate from high school.

Obviously many traumas continue. But dangers have been apprehended. Adaptations have occurred. Further improvements are within reach—and are powerfully desired by all responsible Americans.

And for these things, we must partly thank Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Karl Zinsmeister, who worked for Senator Moynihan in the early 1980s, currently serves in the White House as President George W. Bush’s chief domestic policy adviser.

By Karl Zinsmeister

Remarks to conference “The Moynihan Report Revisited”

American Academy of Political and Social Science

and Harvard University

September 28, 2007

I’m very happy to be here—not least because I’ve been told that the office I occupy at the White House is the same one used for a time by Pat Moynihan during his West Wing years. Karl Rove once tried to explain to me how Moynihan had faithfully extended a long White House tradition by leaving a bottle of whiskey in the office closet for his successor. I seem to recall Karl saying something about Pat carving his initials in the office woodwork too, again extending a hoary old practice.

But I’m afraid that all went in one ear and out the other. I’m not really that kind of conservative, and probably won’t be stashing any traditional bottle or engraving beams during my tenure.

Nor does all of that ring especially true to my ear as Moynihan behavior. The fellow I knew was definitely not to be trusted with a penknife. And if he somehow got hold of one I believe there’s a much higher chance there would have been Irish blood on the rug than initials on the beam.

The whiskey part I think I’ll just skip right over. Although it is possible the dear man may have left behind an empty bottle.

I’d like to state, here at the beginning of my remarks, how appreciative I am to have been included in this distinguished group of researchers, and thinkers, and solvers of national problems. As I scanned the list of presenters at this conference it occurred to me that squirreled away in my personal book collection are perhaps 15 different volumes with one or another of your names on the spine. The persons in this room have taught me—and many other Americans—some of our most important lessons in social policy, and I am honored to share this day with you.

I’m quite certain you could have engaged a more fascinating keynoter, and have to assume my presence here reflects the difficulty of finding someone else who matches the odd Moynihan template: lifelong New Yorker, having a Syracuse connection, with a history of crossing party boundaries, and White House experience slinging domestic-policy advice, to a Texas President. There are only a few of us who can tick that queer combination of boxes, so it may just be runaway historical homage that got me invited here.

In any case, I’m pleased to have this opportunity to pay my respects to the memory of Daniel Patrick Moynihan—who offered me my first job out of college, launching me into the work of Washington. (And please let me enter into the record here that I am speaking for myself, not the President, in all of my remarks today.)

*****

When Teddy Roosevelt said that “nine-tenths of wisdom is being wise in time,” he was thinking of the disappointments of becoming wise too late. Pat Moynihan demonstrated that being wise early also carries certain risks. The thing I most admire Pat for is his work as a kind of intellectual sentinel, as a spotter of significant trends not yet noticed by others, and a ringer of alarms. “He who marries the spirit of the age will soon find himself a widower,” warned Chesterton, and I believe Moynihan’s intellectual fertility grew particularly out of his resistance to fashion and group-think. His personal independence and intellectual autonomy allowed him to cogitate his way through problems without getting distracted by herd movements.

As an example, one of the first projects he set me to work upon as a young Senate aide was research on whether American girls were reaching menarche earlier than females in other times and other societies, and whether this might be an influence on elevated teen childbearing and welfare receipt. I assure you, there weren’t many other Senators or Senate aides clamoring right then for information on precocious menstruation. I had that part of the Library of Congress pretty much to myself. But Moynihan didn’t care if no one else in America could even spell menarche, much less link it to the work of the Senate Finance Committee. If he thought it might be an influence on an important social problem, he wanted to know more.

I don’t want to romanticize, so let me note that Moynihan’s unpredictably ranging mind could often frustrate. There’s a probably apocryphal story about Immanuel Kant and Johann Goethe taking a walk one day to discuss philosophical matters. When they returned, Kant was asked if he found the time enlightening. “I’m still confused,” he is said to have answered, “but at a much higher level.”

There were times when Moynihan confused his colleagues at a very high level, often because he seemed to be of two minds. During his four Senate terms, Moynihan frequently provided talking points for conservatives while voting with liberals. And at times there was some cognitive dissonance.

It reminds me of the father who counseled his daughter, as she headed off to a border-state college, on types of men she might meet. Northern boys, he suggested, were likely to be active and propose interesting dates. Southern boys would often be romantics, perfectly happy to just walk in the moonlight. To which the daughter answered, “I think I’d like to have a Southern boy from as far North as possible.” Sometimes Pat Moynihan seemed to be trying to straddle lines in similar ways.

But for sheer breadth of mind, the man was a delight. Those of us who have resisted the modern tendency toward occupational specialization and instead tried to build careers connecting dots between demographics and economics and religion and history and culture can take comfort from the wide swaths of intellectual life that Moynihan ranged across. My commute to the White House involves bicycling the length of Pennsylvania Avenue every morning and evening, and as I survey the ways that boulevard has revived since the days when Pat Moynihan made rescuing it one of his many projects (back in the early days of the Kennedy administration), I think to myself that this alone would be a pretty good life’s monument.

But of course Moynihan’s accomplishments extended far beyond revitalizing that national corridor, and far beyond his other achievements in architecture and urbanism. He also mastered foreign policy. He was an expert on Social Security. He had a sage’s knowledge of India. He knew more about immigration, and race, and family structure than almost anyone of his generation.

At his best, Moynihan magnified his originality with a tolerance for risk. Those are two very rare—I’m afraid increasingly rare—qualities in Washington. There was a major-league baseball player named Zeke Bonura (who, perhaps fittingly, ended his career in Washington with the Senators) who figured out years ago that under baseball’s rules you usually won’t be charged with an error unless you touch the ball. So Bonura simply avoided any play that looked the least bit difficult, and in this way managed to lead the league in official fielding percentage.

While risk avoidance can yield sterling individual statistics, it is bad for the team—which in the political realm means the nation. Moynihan understood this. In an interview in the spring of 2002 (the last time I saw him in person), I asked why it had become so difficult to build anything new in New York City. He noted that “in the 1970s, civic reputation began to be acquired by people who prevented things from happening,” warning that “many things get stopped for no reason” other than creeping timidity. In his most shining moments, Pat Moynihan was a living advertisement for risks taken in an effort to improve one’s society, and a walking rebuke to those souls unwilling to touch the ball for fear of making a mistake.

*****

Pat Moynihan’s most valuable service to the nation was to point out the central influence of family structure on individual well-being, group prosperity, and collective success. At the tail end of the Baby Boom, Americans were taking family stability for granted, and ignoring the evidence that household decay hurts many innocents, sometimes even dragging down entire communities. The conversation Moynihan started eventually convinced many citizens that the strength of our family bonds isn’t just a private issue, but a matter of essential public interest. His 1965 premise that the federal government should make family stability a central goal of its programs is now shared by widely varied political factions.

A good thing, too, because what the Moynihan Report identified as a minority virus soon became a mass outbreak. Today white families spin apart at rates higher than blacks exhibited at the time he wrote; the two-parent home has become a rarity for African-American children; and the unhappy sequels of disorganized households, absent parents, and unhealthy income gaps have become common. If a young American were placed behind a curtain and you were required to guess his or her social status and individual happiness with only one factual datum before you, the single most trenchant indicator you could ask for would be whether that person grew up with both parents in attendance. Unfortunately, about a third of our next generation will substantially grow up without this advantage, and fully half will have at least a brief brush with family separation before they turn 18.

The rapid spread of the family-decay virus outstripped our abilities to diagnose and prescribe. It’s not that we have stood still since Pat Moynihan dipped his toe in these waters in the mid-1960s. Large efforts have been made to transfer income, encourage work, compensate with public education, bolster responsible fathering, and otherwise mend the tears in our family fabric. These efforts have often been laudable, and sometimes helpful. But they have not made our problems go away.

*****

Of course we must keep trying. One place where I personally nourish hope for solidifying family life today is in efforts to strengthen marriages. The nub of our problem is that large numbers of fathers have become disconnected from their children, and languished in what once would have been called irresponsible bachelor behaviors. For most men, though, active fathering, diligent work, and social responsibility come as part of a package deal that is founded on the male-female dyad. The reality is that once their link to the mother has crumbled, relatively few fathers will stay heavily involved with their children (only 20 to 25 percent in the “Fragile Families” research, and less in some other studies). Similar falloffs appear in the upholding of other obligations and responsibilities.

The strongest influence leading most men to grow up and join the world is the desire to win a good lifemate. Hunger for a strong mental, emotional, and sexual partnership with a woman is the main force creating the good husband, good father, good employee, and good citizen. Conversely, in a world where marriages are falling apart, desirable male qualities like respect for women, mentoring of children, disciplined occupation, and social responsibility will also go into decline. And attempts to fix those secondary breakdowns without first fixing the marriages will not be very efficient. To put it simply: no solid marriage, no good family man.

More generally, psychologists and social historians like J. D. Unwin have suggested that rechannelling sexual energy into less self-interested undertakings—into constructive social activity—is a hallmark of successful civilizations. The institutions that do the rechannelling are invaluable to society. And the most necessary institution of all for accomplishing this is marriage.

Marriage also functions as a safety net for individuals. Evidence from history, examples from particular sub-populations, and patterns among immigrants suggest that where the marriage base is solid, households can weather economic setbacks and external pressures surprisingly well. But when loyalty to spouse and fellow parent crumbles, even a minor battering can bring misery.

The best antidote to the various social turmoils Moynihan worried over, then, may be renewed emphasis on enduring marriage. Yet any observer who pursues that proposition will quickly be struck by one thing: How little help is currently offered by society to reinforce marriage. The last I checked, research indicated that only about a fifth of all divorced persons received any sort of counseling or mediation before dissolving their marriage. Meanwhile, only about a third of all couples receive any formal marital guidance before exchanging vows. Pretty clearly, we have not done all we can to strengthen marriage as a vital civic institution.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer once counseled a young husband and wife that “it is not your love that sustains the marriage, but from now on the marriage that sustains your love.” That paradox is actively resisted by many proponents of today’s pleasure culture, who portray love as a feeling, rather than as a decision to befriend and stand by someone for the long term. In truth, however, marital stability need not conflict with pleasure. By keeping couples together, after predictable stresses arise, long enough to give them a chance to fall in love again, committed marriage actually serves individual delight and happiness.

I recognize that these notions are hard for some modern Americans to accept. The family-structure concerns that Pat Moynihan introduced into public consciousness 40 years ago are still being squelched with claims that family life is a matter of merely “private” concern—the business only of the persons directly involved. On both the left and the right there is a temptation to ignore contentious family issues in favor of more bloodless explanations for social problems.

On the political left, an automatic trope blames social problems and disparities on discrimination, with easy recourse to government action or the courts as the favored solution. Lapsing into this simplistic explanation, however, would undo the heroic Moynihan achievement—which was to make the nation understand that civil-rights guarantees alone will never be enough to pull lagging populations into mainstream success.

On the political right, the symmetrical mistake is believing that national prosperity is all that’s needed to erase social fractures. The truth is that the full-employment economy Moynihan dreamed about has mostly been a reality in the U.S. for more than a decade. My White House duties have included some intense work on immigration issues, and I can tell you that our most pressing economic risk today is not having too few jobs, but rather having too few willing workers for the jobs that need filling. Yet even as employers clamor, some U.S. sub-groups languish outside the mainstream workforce—for other than economic reasons.

Here is Moynihan reflecting—20 years later—on his mid-1960s insight: “The quality and decency of life in the United States…were incomparably greater than in years past. And yet there was a segment of our population whose lives had somehow not been touched by the general success…. Increasingly, family structure defined this population.”

*****

This problem has deepened in the years since, and shows up in many places. Here is one little example that whispers a warning to us: While children of divorce make up close to half of all American youth today, they are only around 10 percent of the students who enter our most demanding colleges. Even after adjusting for income, SAT scores, parental education, and so forth, children who experience divorce are only half as likely to attend a selective college. Clearly, many young Americans are seriously weighed down by their parents’s family choices, in ways that can be hard to overcome.

This is perhaps the deepest root of today’s inequality problem. Widened gaps between the most successful and least successful Americans rightly worry both liberals and conservatives at present. The weakening of family cohesion, and the damage this does to our nation’s “human capital,” especially children, is clearly a major driver of these disparate life courses.

I also worry, personally, about an even broader problem: the possibility that raising children itself may now yield economic disadvantages. Even steady workers and loyal spouses sometimes feel today that acting as a devoted parent can leave you behind other Americans in standard of living. Certainly changes in taxation have punished investment in children.

At the beginning of the Baby Boom, a typical married-couple family with two children paid only a few percent of its income in taxes. There was a consensus that parents rearing young children were providing an important service to society, and ought not be burdened with heavy taxes. Today, the typical family of four has more than a third of its income consumed by Federal income taxes, payroll taxes, and state and local taxes. It’s sobering to realize that the typical family now pays more in taxes than it pays for mortgage, health insurance, and transportation combined.

In the second half of the twentieth century, taxes rose much more sharply on families with children than on the childless. This primarily reflects the decline of the dependent exemption in our income tax system, plus rising Social Security levies. Recent tax cuts have trimmed the rate of Federal taxation on the median family of four by about 30 percent since the 1981 tax peak, but the tax demands on childrearers remain far higher today than during the first two decades after World War II. If the dependent exemption were set at the same fraction of income as in 1948, a parent could now write off about $15,000 for every child—instead of the $3,300 allowed by the IRS last year.

The expanded tax burden on families is exacerbated by recent upward spirals in the price of particular goods and services that are central to family life. For instance, families with children need more living space than other Americans, so the housing bubble that rocketed home prices upward over a decade has pinched parents even more than others. Medical care is likewise something consumed by all citizens but in higher quantities by childrearing families, so, here too, a generation of exaggerated cost spikes has pressed doubly hard on parents. A final inflationary spiral especially disadvantaging Americans raising kids is college costs—which soared by almost 300 percent over the same recent period when medical expenses jumped 200 percent, food rose 80 percent, and clothing inflation was 20 percent.

The cumulative effect of these economic turns has been to leave families feeling less well off. At the same time, an economic boom lasting nearly a generation has offered child-free Americans record prosperity and opportunities for consumption. Adjusting the economic advantages of non-childrearers versus childrearing households may be a task future policymakers will want to consider.

Mind you, this is not a matter of pitting one group of Americans against another, because nearly all us spend many years in both kinds of households. The question is simply whether it would be good for the nation if a certain amount of economic burden could be shifted off the shoulders of those raising children while they are in the middle of what has aptly been called “the parental emergency.” That would of course mean transferring some load elsewhere—to those same Americans during the years before and after they focus on children, as well as to the small number of Americans who never raise children. Since childrearers are not only producing America’s future citizens and inventors and soldiers, but also the workers who will pay the Social Security and Medicare bills of today’s footloose adults, offering support and encouragement to parents would seem to be not only fair but also sensibly businesslike. Parents are the ones who keep social-welfare transfer systems solvent in the long run.

*****

I’d like to end on something of a positive note. Not to make you feel good, but because pessimism about American society usually ends up being embarrassingly inaccurate. Just as an empirical fact, the reality of U.S. history has been that most of this country’s social and political problems have eventually ended up improving—often in surprising and speedy ways. As I re-read “The Negro Family” for this conference, I couldn’t help but feel that Moynihan’s report was somewhat over grim in ways that date it and make it less “true.”

His set-up to the report’s final paragraphs famously warns that “the tangle of pathology is tightening.” And in 1965 it still was. But just a half-generation later, few observers believe, as then, that “this problem may in fact be out of control.”

The tide toward welfare dependency that once seemed irresistible has crested. More than half of all African-Americans now own their own homes. A traumatic national crime surge has been tamped down. Six out of ten black youths are in college the year after they graduate from high school.

Obviously many traumas continue. But dangers have been apprehended. Adaptations have occurred. Further improvements are within reach—and are powerfully desired by all responsible Americans.

And for these things, we must partly thank Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Karl Zinsmeister, who worked for Senator Moynihan in the early 1980s, currently serves in the White House as President George W. Bush’s chief domestic policy adviser.